According to author Victoria Wilson, Barbara Stanwyck was a big admirer of Ann Harding and had once said about her: "There are only a few actors who can get me sufficiently to make me lose myself in the story. Ann Harding is one of them ... Miss Harding is so entirely natural at all times that she makes me believe in her and what she is doing. I have always hoped that my own work shows the same degree of sincerity. When I see an Ann Harding picture nothing but her work and the story interests me."

Born Dorothy Walton Gatley in 1902, Ann Harding started her acting career in the theatre and in the 1920s enjoyed several successes on Broadway, particularly with The Trial of Mary Dugan (1927). In 1929, she left the New York stage for Hollywood, making her film debut opposite Fredric March in Paris Bound (1929). Because of her stage experience and good diction, Ann was a sought-after actress in the early days of the talkies. She was put under contract at Pathé, later RKO, and promoted as the studio's answer to MGM's Norma Shearer. For her role in her fourth film Holiday (1930) Ann earned an Oscar nomination and with films like The Animal Kingdom (1932), When Ladies Meet (1933) and Double Harness (1933) she further established herself as one of the most popular leading ladies of the early 1930s.

Ann's popularity would drastically decline after 1935. Audiences grew tired of her being typecast as the noble, self-sacrificing woman, and also critics were responding less favourably to her work. In 1936, Ann retired from acting following a bitter court fight with her first husband —actor Harry Bannister (m. 1926-1932)— over the custody of their daughter Jane. She married conductor Werner Janssen in 1937 (m. until 1962) and eventually returned to the screen in 1942 with a role in the thriller Eyes in the Night. Other supporting roles followed, most notably in It Happened on 5th Avenue (1947) and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956). During the latter part of her career —Ann kept working until the mid-1960s— she did some television work and also returned to the stage after an absence of more than 30 years. Ann died in September 1981, aged 79.

|

| Beautiful, elegant Ann Harding left different impressions on those she had worked with. Laurence Olivier called her "an angel", director Henry Hathaway said she was "an absolute bitch", while Myrna Loy thought she was "a very private person, a wonderful actress completely without star temperament, but withdrawn." |

.jpg) |

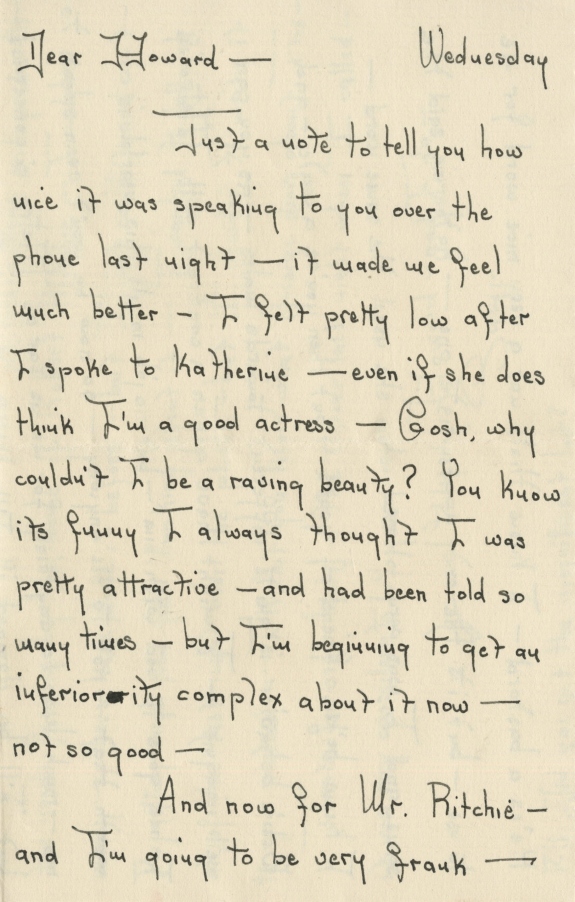

Ann Harding in six of her films, clockwise with Mary Astor in Holiday (1930), Leslie Howard in The Animal Kingdom (1932), Myrna Loy in When Ladies Meet (1933), William Powell in Double Harness (1933), Robert Montgomery in Biography of a Bachelor Girl (1935) and Gary Cooper in Peter Ibbetson (1935). I first saw Ann in Double Harness and was immediately impressed by her. I love her calm and sophisticated demeanor and especially her natural style of acting made me want to see more of her. Having now seen 19 Ann Harding films, my favourites remain Double Harness and When Ladies Meet.

___________

|

Ann Harding hated being a celebrity and also hated giving interviews, which made her very unpopular with the press (read more in this post). She disliked Hollywood and once said: "I loathed the stupidity in the handling of the material in Hollywood." And about the studio system she commented: "

If you're under contract when you're making pictures you may get the plums, but they own your soul. If you're not under contract, you have to take your chances."

Despite having been a big star in her day, Harding has been largely forgotten by contemporary audiences. To keep her legacy alive, author Scott O'Brien wrote a biography entitled Ann Harding - Cinema's Gallant Lady, published in May 2010. Several months after the publication of his book, O'Brien received a letter from Ann's niece Dorothy Nash Wagar, daughter of Ann's sister Edith. Ann had been an intimate part of her niece's world when Wagar was aged 7-13. In her letter Wagar thanks O'Brien for his book and also shares childhood memories of her "Aunt Dody".

November 15, 2010

Dear Scott,

I am more than happy to recall events in my childhood in relationship with my aunt Dody, better known as Ann Harding. First, I want to take this opportunity to thank you for your outstanding book, in which you documented her meteoric rise to stardom in the thirties, and the balance of her career and life.

My family moved from New York to California in 1930, at her invitation so my father could manage her finances. It was a momentous time for my sister Barbara and me. The train trip, all the sights and sounds, the extraordinary differences of the East Coast vs. the West. For me it was a chance to see my little cousin, Jane, but most of all, my aunt for whom I was named and my Godmother.

The days at my aunt's home were a delight, playing with Jane, swimming and wandering about the hillside. When I lived with her and Jane for a time, my aunt invited Bonita Granville to come swim with Jane and me every day. Bonita was about my age and a lovely chum, and she showed me how to dive off the diving board which was a big event for me. Although Aunt Dody was gone most of the day, as soon as she'd come home, we'd all gather in the living room to talk over the events of the day. At all times she was interested in what had happened, and was very loving with us.

My fondest memories of Aunt Dody are small things, really. Watching her brush her hair and then twist it into that bun was an astonishing sight. She was so fast at it, I could hardly believe my eyes. After she'd wash her hair, she'd sit out on the patio and read while the sun dried it. Another favorite memory of mine is how she'd tuck herself away in her small den downstairs. There was a piano and a chair with a writing desk where she spent some of her free hours writing. She also enjoyed playing the piano, gardening, swimming, tennis and crocheting.

I think that my aunt's first love was music. By the age of two, she'd learned to play a song on the piano my grandmother had written for the girls. Aunt Dody sang Gilbert and Sullivan songs while she was crocheting -she taught me several of them, and how to harmonize, and we'd have the most fun singing Chippy-chippy-chopper-on-a-big-black-block. She had a wonderful sound system -music played throughout the entire house. The record player was right behind the piano in a little cabinet built into the wall. We listened to the radio, too, but mostly records -Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, Wagner. She gave me several books on music, and her greatest gift to me was the appreciation of it.

I was almost in my aunt's movie, Westward Passage, in the role as her daughter. Costumes had been made, and the first day of filming was upon us -but the weather was terrible, holding up the production. Sir Lawrence Olivier was the dearest man, and even danced with me as we waited for the weather to clear, but it never did. The next day Aunt Dody came home and called me into the living room. She sat next to me on the couch, and tenderly let me know that I wouldn't be in the movie after all. The mother of a young actress had complained of nepotism. The silver lining was that my chum, Bonita got the role, and that took the sting out of it.

My favorite movies were Biography of a Bachelor Girl, and Peter Ibbetson. I loved them for different reasons. In Biography of a Bachelor Girl, it was fun to see Aunt Dody's comical side, which we always saw at home. She was so funny she'd have all of us in stitches— Jane, Fong, the butler, and me. Peter Ibbetson is such a beautiful story, and the especially wonderful spark in her eyes that I recall so dearly is eminently present.

Recalling the words my mother wrote of her sister's devotion to her art -that she was essentially a pilgrim in her great humility and reverence, seeking what every artist must have -love of work for the work itself. She approached everything with the same brilliant life force. Ann Harding was a remarkable actress, a wonderful person, a loving aunt. Thank you for keeping her spirit alive.

Sincerely,

Dorothy Nash Wagar

Source: scottobrienauthor.com

|

| Ann Harding with her daughter Jane by her first husband Harry Bannister. The two were very close when Jane was little. However, they later became estranged and when Ann died in 1981 they hadn't spoken for years. |

|

| Ann with her sister Edith Nash in 1935. At some point Ann stopped speaking to her sister and they became estranged (like Ann and her daughter— makes you wonder what happened?!). Before her death Ann tried to find her sister to make amends. When Dorothy Nash Wagar found out that Ann had tried to contact her mother near the end of her life, it meant a lot to her: "After years and years of their not having any discourse tears came to my eyes, because I was so happy and relieved to think that that happened. Aunt Dody must have undergone quite a change with regard to her relationship with my mother and wanted to get in touch with her. I wish my mother had known that." |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)