Helen Hayes and Joan Crawford became friends in the 1930s. In her (third) memoir My Life in Three Acts (1990) Hayes said that Joan had adopted her as her best friend, despite the fact that they were very different. Joan probably didn't feel threatened by her, Helen thought, not considering her a rival. In any case, Helen was fascinated by the glamorous Joan and the two women entered into an unlikely friendship.

According to her memoir, Hayes didn't see much of Joan anymore after Joan became involved with Pepsi-Cola, while Hayes herself was busy working in the theatre. (In 1955, Joan married Alfred Steele, president of Pepsi-Cola, and after Steele's death four years later she became a board member of Pepsi, to eventually retire in 1973.) Nevertheless, the women would still meet on occasion and also sent each other telegrams/letters. In her 1962 autobiography, Joan said that she and Helen were "staunch friends, sometimes only by letter". Below is some of Helen's correspondence to Joan from the 1970's, clearly showing that Joan never forgot her friends. .jpg) |

| Sources: letter above left The Concluding Chapter of Crawford and the two other letters The Best of Everything: A Joan Crawford Encyclopedia |

"Joan was not quite rational in her raising of children. You might say she was strict or stern. But cruel is probably the right word. [...]

When my young son Jim came to stay with me, we would go out to lunch with them [Joan and her son Christopher]. Joan would snap, “Christopher!” whenever he tried to speak. He would bow his little head, completely cowed, and then he’d say, “Mommie dearest, may I speak?” Joan’s children had to say [that] before she allowed them to utter another word. It would have been futile for me or anyone else to protest. Joan would only get angry and probably vent her rage on the kids.

On one of my Hollywood trips about this time, I ran into Dinah Shore in the hairdressing department of MGM. She beckoned me to come over, and then began talking in a whisper. “Helen, everybody knows that you’re Joan Crawford’s close friend. Can you do something about her treatment of those children? We’re all worried to death.” ... Well, I was frightened to do it. We were all afraid of Joan – which is the biggest problem in this kind of situation, as we’ve seen with fatal results. No one would speak up.

I have read that people who are abused as children often become abusive parents. Maybe it was Joan’s tough childhood that made her exert her power like that over her own children. But understanding the reason did not make their suffering any easier to watch."

|

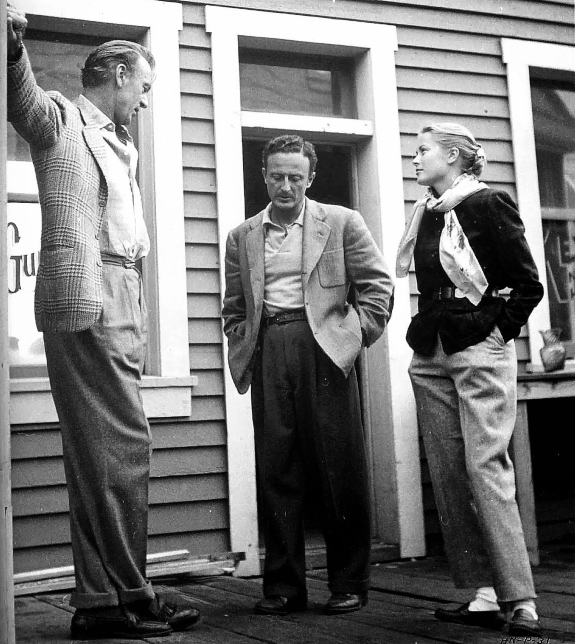

| (l to r) ca. 1956, Helen Hayes, Alfred Steele, Joan Crawford and James MacArthur; Steele was Joan's fourth husband and MacArthur was Hayes' adopted son. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)