During his career Alfred Hitchcock made only one film for Twentieth Century-Fox. In late 1942, while under contract to David Selznick, Hitchcock was loaned out to Fox for a two-picture deal, the deal having been closed with Selznick by Fox executive William Goetz. (Goetz was Selznick's brother-in-law and temporarily replaced studio boss Darryl Zanuck who served in the Army Signal Corps.) The picture Hitchcock made for Fox was

Lifeboat (1944) —the second Fox picture was never made— based on a story by John Steinbeck and starring Tallulah Bankhead, William Bendix, Walter Slezak and John Hodiak. (For the plot of the film, go

here.)

In the summer of 1943, with pre-production of Lifeboat in full swing, Darryl Zanuck returned from military service. While he was usually involved in the scripting of Fox's A-films, in his absence Lifeboat was written by Jo Swerling (the only one eventually credited), John Steinbeck, Alma Reville (Hitchcock's wife) and Hitchcock himself. Upon his return Zanuck found Hitch firmly in charge, with producer Kenneth Macgowan more or less acting as the director's assistant. In August 1943, filming on Lifeboat finally began. Zanuck was not happy, however, feeling the pace was too slow and the screenplay too long.

On 19 August, Zanuck wrote a joint memo to Hitchcock, Macgowan and Swerling, saying that he had the script timed with a stopwatch and that, according to his calculations, the finished film would last almost three hours. "Drastic eliminations are necessary", he said, and they had to be prepared "to drop some element in its entirety". Annoyed by Zanuck's missive, Hitchcock replied the next day, his memo to Zanuck seen below ("I have never encountered such stupid information as has been given you by some menial who apparently has no knowledge of the timing of a script..."). Zanuck answered Hitch the same day (on 20 August), his memo to be read below as well. (Zanuck's first memo from 19 August is not shown.)

The finished film eventually ran 97 minutes and cost a little over 1.5 million dollars. Despite Zanuck's complaints, Hitch was able to complete Lifeboat with little interference from the studio boss. In September 1943 when Zanuck saw the first reel of the film he was enthusiastic and later called Lifeboat "an outstanding film with awards potential". The picture would receive three Academy Award nominations, i.e. for Hitchcock (Best Direction), Steinbeck (Best Story) and Glen MacWilliams (Best Cinematography) but no one won. Although Lifeboat was a box-office flop, it is now considered an underrated entry in Hitchcock's impressive oeuvre.

|

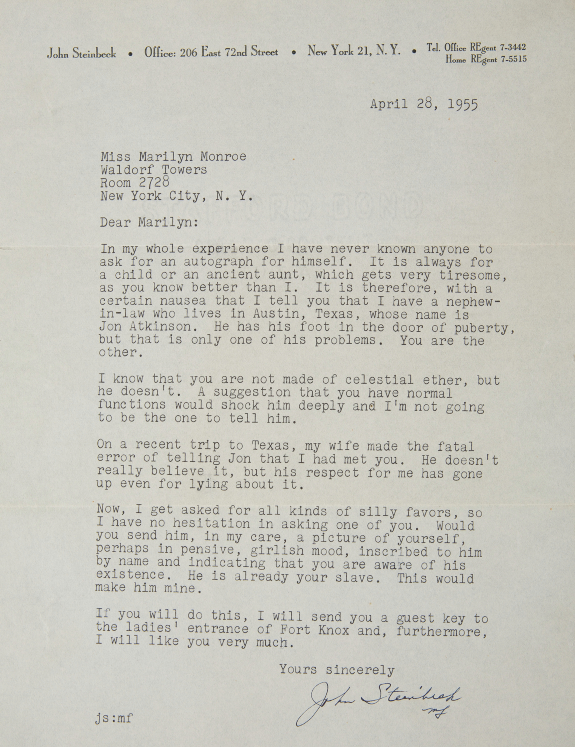

| Above: Alfred Hitchcock on the set of Lifeboat. Below: Part of the Lifeboat cast with (from left to right) Mary Anderson, Hume Cronyn, John Hodiak, Tallulah Bankhead, Henry Hull and Canada Lee. |

Dear Mr. Zanuck:

I have just received your note regarding the length of LIFEBOAT. I don't know who you employ to time your scripts, but whoever did it is misleading you horribly. I will even go so far as to say disgracefully. In all my experience in this business, I have never encountered such stupid information as has been given you by some menial who apparently has no knowledge of the timing of a script or the playing of dialogue.

According to the note, in paragraph two you express your opinion, based upon this ridiculous information, that the picture will be 15,000 feet in length. I can only think that the person who did this for you is trying to sabotage the picture. Maybe it is a spy belonging to some disgruntled ex-employee.

Now let us get down to facts, and let us base our calculations on facts that come from persons of long experience and also the fact of actual shooting time. Through Page 28 of the script, which includes a fair amount of silent action, the shot footage is actually timed at 15 minutes. This, on the basis of a 147-page script, works out to actually 79 minutes. Add to this a maximum of 5 minutes, (which is generous for the storm sequence), we arrive at an extremely generous estimate of 84 minutes. Films run through at 90 feet a minute. Therefore, we arrive at a length of 7560 feet, which, in my opinion, is considerably inadequate for a picture of this calibre and importance.

I am gravely concerned at the suggestion of cutting the story for fear that after the shooting is completed we will find that the picture is so short that we will have to commence writing added sequences to make the picture sufficiently long for an important release.

In view of our previous discussions regarding the shooting time, I would like to repeat that we are all considerably misled by the cumbersome methods of shooting on an exterior stage which could never be repeated under normal conditions in the studio. As I pointed out to you in our previous conversation, I am at present shooting a sequence of 9 pages which will take approximately 2 days - which is exactly one day under the allotted time in the production schedule.

Dear Mr. Zanuck, please take good note of these above facts before we commit ourselves to any acts which in the ultimate may make us all look extremely ridiculous by giving insufficient care and notice to these considerations.

Your obedient servant,

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

__________

My dear Hitchcock:

The timing of the script was not done by an expert, nor by anyone who was deliberately attempting to mislead us. One person merely read the dialogue aloud, while the other person took down the timing with a stop-watch. Now, of course, they did not overlap any dialogue, and they might have read slowly, or they might have paused too long between speeches, and, of course, they are not aware of any of the cuts in dialogue or script pages that we have recently eliminated.

According to your calculation, the script will run to 7,500 feet. I will bet you $1,000, the winner to donate the amount to charity, that you are wrong by 2,000 feet. I am now speaking about the script as it stands, and I believe I am allowing myself plenty of footage for protection.

A picture of this scope, in my opinion, should hold up very well at 9,000 feet, and perhaps even longer, but if we actually are over 10,000 feet, then I know that you agree the matter is serious, not only from the standpoint of economy.

You are making excellent progress, and certainly no one could complain about the amount of film you have exposed in the last few days.

It still remains my opinion, however, that our story is repetitious in places, and monotonous. I am certain that the cuts we have made in the last few days have not harmed the quality of the production one iota. As a matter of fact, I feel that they have been helpful [...]

I do not make a habit of interfering with productions placed in such capable hands as yours. Any interference in this case comes from an emergency problem, which I inherited. On all sides, I have been advised to call off the production. The picture was devised originally, so I understand, to be a million dollar cost project. Suddenly its cost has doubled, and no one could possibly dislike the idea of butting in any more than I do. I have plenty of worries on my own personal productions, and nothing would give me greater joy than to forget all about LIFEBOAT until the night I go to the preview.

You felt you could make the picture in eight or nine weeks. You told me so. Lefty Hough [Fox's production manager] thought that you could. He told me so, and so did Macgowan. We took into consideration this fact, and arrived at a fair budget. We were all wrong. It would be folly now, in my opinion, to butcher the story in an effort to save a penny here and there, but it is also folly to fail to study each scene, each line and each episode, and see if we cannot find ways and means to eliminate non-essentials.

Darryl

Source of both memos: Hitchcock's Notebooks: An Authorized And Illustrated Look Inside The Creative Mind Of Alfred Hitchcock (1999) by Dan Auiler.

|

| Darryl F. Zanuck in his military outfit |