|

| Irving Thalberg, Lillian Gish and Louis B. Mayer in 1926 |

.jpg) |

| Thalberg won the Oscar for Best Picture for Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), here photographed with Clark Gable and director Frank Capra at the Oscars of 1936. Click here to see and hear Thalberg accept the award from Capra. Thalberg had won the Best Picture Oscar twice before, for The Broadway Melody (1929) and Grand Hotel (1932). |

Dear Irving:

I cannot permit you to go away to Europe without expressing to you my regret that our last conference had to end in a loss of temper, particularly on my part. It has always been my desire to make things as comfortable and pleasant for you as I knew how, and I stayed away from you while you were ill because I knew if I saw you it was inevitable that we would touch on business, and this I did not want to do until you were strong again. In fact I told Norma [Shearer] to discourage my coming to see you until you felt quite well.

It is unfortunate that the so-called friends of yours and mine should be only too glad to create ill feeling, and attempt to disrupt a friendship and association that has existed for about ten years. Up to this time they have been unsuccessful, but they have always been envious of our close contact and regard for each other.

If you will stop and think, you cannot mention a single motive or reason why I should cease to love you or entertain anything but a feeling of real sincerity and friendship for you. During your absence from the Studio, I was confronted with what seems to me to be a Herculean task, but the old saying still goes —“The show must go on.” Certainly we could not permit the Company to go out of existence just because the active head of production was taken ill and likely to be away from the business for a considerable length of time. I, being your partner, it fell to my lot, and I considered it my duty and legal obligation under our contract, to take up the burden anew where you left off, and to carry on to the best of my ability . . . .I regret very much that when I last went to see you to talk things over I did not find you in a receptive mood to treat me as your loyal partner and friend. I felt an air of suspicion on your part towards me, and want you to know if I was correct in my interpretation of your feeling, that it was entirely undeserved. When I went to see you I was wearied down with the problems I have been carrying, which problems have been multiplied because of the fact that the partner who has borne the major portion of them on his shoulders, was not here. Instead of appreciating the fact that I have cheerfully taken on your work, as well as my own, and have carried on to the best of my ability, you chose to bitingly and sarcastically accuse me of many things, by innuendo, which I am supposed to have done to you and your friends. Being a man of temperament, I could not restrain myself any longer, and lost my temper. Even when I did so I regretted it, because I thought it might hurt you physically.

Regardless of how I felt, or what my nervous condition was, I am big enough to apologize to you, for you were ill and I should have controlled my feelings.

I am doing everything possible for the best interests of yourself, Bob [MGM attorney Robert Rubin], myself, and the Company, and I want you to know just how I feel towards you; and, if possible, I want you to divest yourself of all suspicion, and believe me to be your real friend, and to know that when I tell you I have the greatest possible affection and sincere friendship for you, I am telling the truth.

I hope this trip you are about to make will restore you to even greater vigor than you have ever before enjoyed, and will bring you back so that we may work together as we have done for the past ten years.And now let me philosophize for a moment. Anyone who has said that I have a feeling of wrong towards you will eventually have cause to regret their treachery, because that is exactly what it would be, and what it would be on my part if I had any feeling other than what I have expressed in this letter towards you. I assure you I will go on loving you to the end.

I am going to take the liberty of quoting a bit of philosophy from Lincoln. This is a quotation I have on my desk, and one which I value highly: “I do the very best I know how, and the very best I can, and I mean to keep doing so until the end. If the end brings me out right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything. If the end brings me out wrong, ten angels swearing I was right, will make no difference.”

I assure you, Irving, you will never have the opportunity of looking me in the eye and justly accusing me of disloyalty or of doing anything but what a good friend and an earnest associate would do for your interest, and for your comfort.

If this letter makes the impression on you that I hope it does, I should be awfully glad to see you before you go and to bid you Bon Voyage. If it does not, I shall be sorry, and will pray for your speedy recovery to strength and good health.

With love and regards, believe me,

Faithfully yours,Louis

Thalberg responded two days later.

Dear Louis:

I was deeply and sincerely appreciative of the fact that you wrote me a letter, as I should have been very unhappy to have left the city without seeing you. I was indeed sorry that the words between us should have caused on your part a desire not to see me, as I assure you frankly and honestly they did not have that effect on me. We have debated and disagreed many times before, and I hope we shall many times again. For any words that I may have used that aroused bitterness in you, I am truly sorry and I apologize.

I’m very sorry that I have been unable to make clear that it has not been the actions or the words of any—as you so properly call them—so-called friends, whose libelous statements were bound to occur, that have in any way influenced me. If our friendship and association could be severed by so weak a force, I am sure it would long ago have been ruptured by that source. There are, however, loyalties that are greater than the loyalties of friendship. There are the loyalties to ideals, the loyalties to principles without which friendship loses character and real meaning, for a friend who deliberately permits the other to go wrong without sacrificing all—even friendship—has not reached the truest sense of that ideal. Furthermore, the ideals and principles were ones that we had all agreed upon again and again in our association, and every partner shared equally in the success that attended the carrying out of those principles.

I had hoped that the defense of those principles would be made by my three closest friends [presumably Mayer, Schenck and Rubin]. I say this not in criticism, but in explanation of the depths of the emotions aroused in me, and in the hopes that you will understand. I realize with deep appreciation the effort you have been making for the company and in my behalf, and no one more than myself understands the strain to which you are subjected.

Believe me, you have my sympathy, understanding and good wishes in the task you are undertaking; and no one more than myself would enjoy your success, for your own sake even more than for the sake of the company.

Please come to see me as soon as it is convenient for you to do so, as nothing would make me happier than to feel we had parted at least as good personal friends, if not better, than ever before.

Irving

Source: Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince (2009), by Mark A. Vieira

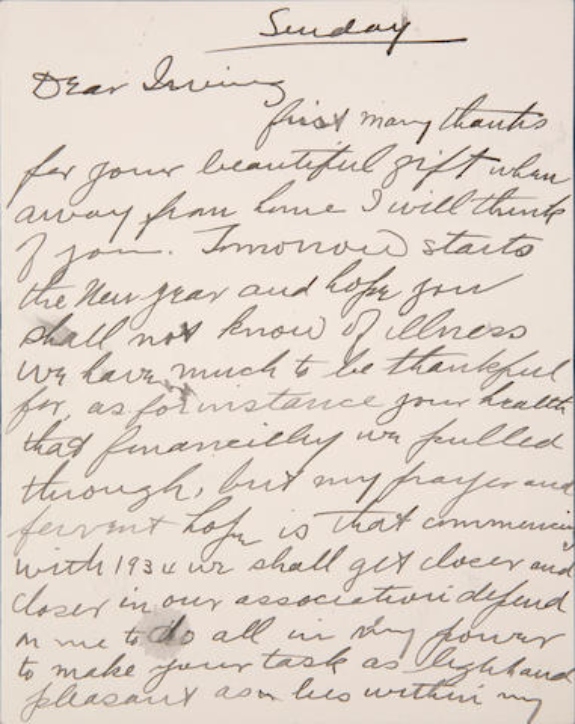

Despite their broken friendship, Thalberg and Mayer remained civil and polite to each other, at least in their letters. Not only the letters above show the courtesies between them, but also the following letter written by Mayer to Thalberg on 31 December 1933. Mayer expresses his wish to "get closer and closer in [his] association" with Thalberg in the new year, and also says he will do anything to make Thalberg's work "light and pleasant". However, it was Mayer who stonewalled Thalberg in preparing his first films as a unit producer. Thalberg found that writers and actors he wanted to work with were suddenly unavailable, assigned elsewhere by Mayer. Also, Mayer had blocked Thalberg's access to MGM's best directors, so for Riptide (1934) Thalberg had to look outside the studio and eventually hired freelancer Edmund Goulding.

|

| Thalberg with wife Norma Shearer and Mayer in 1932 |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)