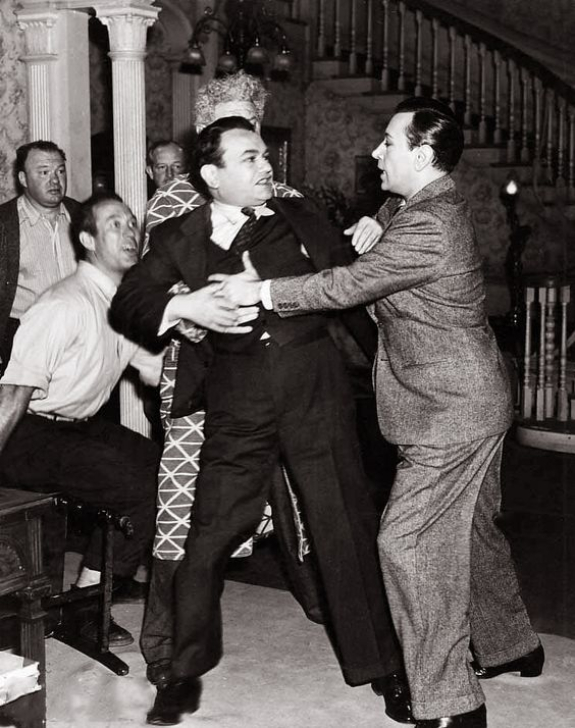

In April 1941, production of Raoul Walsh's Manpower was held up by two incidents involving the film's principal actors Edward G. Robinson and George Raft. During the first incident on 18 April, Raft verbally abused Robinson following a disagreement about a line of dialogue. A week later, on 26 April, Raft again engaged in verbal abuse and also pushed Robinson around on the set, this time witnessed by a photographer from Life magazine whose photo of the incident appeared in Life's May 1941 issue. Raft's feelings of animosity towards Robinson reportedly stemmed from his being third billed —Robinson received top billing and leading lady Marlene Dietrich second billing— despite having the largest role in the film. Also, Raft was infatuated with Dietrich and believed he had a rival in Robinson.

On 30 April 1941, Roy Obringer (head of Warner Bros.' legal department) wrote the following letter to the Screen Actors Guild, giving a detailed description of the two incidents as mentioned above. The dispute between Robinson and Raft was eventually settled by SAG, after which the film was completed. While the two men buried the hatchet years later —they would star in one more film together, A Bullet For Joey (1955)— in his 1973 autobiography All My Yesterdays Robinson maintained that Raft was "touchy, difficult and thoroughly impossible to play with."

Screen Actors Guild

care, Kenneth Thomson, Executive Secretary,

1823 Courtney Avenue

Los Angeles, California

April 30, 1941

Gentlemen:

On or about March 24, 1941, the undersigned corporation commenced photography on its motion picture entitled Manpower, with Edward G. Robinson, Marlene Dietrich, and George Raft, as principal players... As production on this motion picture progressed it became apparent to a number of persons engaged in and about the production that a feeling of hostility was being evidenced by Mr. Raft against Mr. Edward G. Robinson... The situation culminated in an unusually heated and disagreeable verbal attack by Mr. George Raft upon Mr. Edward G. Robinson on 18 April, 1941, on the premises of the undersigned Company at Burbank, California, and immediately outside Stage No. 11, on which the production was then being photographed... The controversy at that time appeared to arise over the inclusion or deletion of a certain line of dialogue in the final script covering said photoplay. Apparently, Mr. Raft was of the opinion that the line should not be spoken, although assigned to Mr. Robinson, whereas Mr. Robinson took the view that the line was in the script and was satisfactory to him, and that inasmuch as he considered the line an important one, he preferred to speak the line. Mr. Robinson then said, in substance, to Mr. Raft, "Look, George, you may think the line does not make any sense, but I have to speak it and it is all right with me." Thereupon, in the presence of the persons above named, and perhaps in the presence of other persons engaged on said production, Mr. George Raft directed toward Mr. Robinson a volley of profanity and obscene language with the express purpose and intent of embarrassing and humiliating Mr. Robinson and lowering his professional dignity and standing in the eyes of all those persons with whom he was obliged to work and come in contact in connection with the production of said photoplay.

In the opinion of those persons to whom representatives of the undersigned corporation have talked, the attack on Mr. Raft's part was wholly uncalled for and actually brought about a very serious disturbance in the production of said photoplay. The interruption and disturbance of production of the picture became so serious because of the situation that Mr. Hal B. Wallis, Executive Producer of the undersigned corporation, was called into the controversy, Mr. Edward G. Robinson left the set and went to his dressing room, and the entire production was stopped for several hours, resulting in a great and substantial loss to the undersigned. Several hours after the controversy had been temporarily quieted, production was proceeded with and approximately a week passed and, except as called for by the script and by the Director, Messrs. Robinson and Raft did not speak to one another, although the script proceeded upon the theory that the characters portrayed by Messrs. Robinson and Raft were close friends.

Just prior to twelve o'clock noon on Saturday, April 26th, while the cast in said production was engaged on said Stage 11, Mr. Robinson was rehearsing a scene wherein the script called for him to be provoked by one of the other characters. The script called for Mr. Robinson to attack this character and during the attack the script required that Mr. Raft, playing the part of "Johnnie" in the production, make his entrance and seek to quiet the disturbance. Instead of conducting himself as called for by the script, Mr. Raft immediately undertook to and did violently rough-house and push the said Edward G. Robinson around the set in an unusually vigorous and forceful manner, with the showing of a great deal of personal feeling and temper on Mr. Raft's part, causing Mr. Robinson to wheel around and say to Mr. Raft, "What the hell is all this?" In reply to Mr. Robinson's question to Mr. Raft, Mr. Raft thereupon told Mr. Robinson to "shut up", and in the immediate presence of the persons hereinafter mentioned, directed toward him a volley of personal abuse and profanity, and threatened the said Edward G. Robinson with bodily harm, and in the course of his remarks directed and applied to Mr. Robinson in a loud and boisterous tone of voice, numerous filthy, obscene and profane expressions. Thereupon, Mr. Robinson walked into his dressing room on the set. A minute or so later Mr. Robinson returned to the set and addressed himself to Mr. Raft, substantially as follows: "George, what a fool you are for carrying on in such an unprofessional manner. What's the use of going on? I have come here to do my work and not to indulge in anything of this nature. It seems impossible for me to continue." Following such remarks Mr Raft directed another volley of profanity and obscene language toward Mr. Robinson, whereupon Director Raoul Walsh, Assistant Director Russell Saunders, and others, fearing further personal violence on the set between the two men, jumped in and separated them, and Mr. Edward G. Robinson left for his dressing room off the set and the entire production was stopped...

As a result of the controversy between the two Principals on Stage 11, all further work involving the two principals was suspended from just prior to noon on Saturday, April 26, 1941, until Monday morning, April 28, 1941, and the general confusion, etc., on the set was such that the undersigned corporation lost an entire day in production, resulting in a large financial loss to the undersigned corporation. The effect of the disturbance was such that Mr. Robinson became highly nervous and such nervous condition affected his voice and made the same husky so that he was unable to properly and clearly speak his lines and otherwise give the artistic and creative performance of which he is capable. The said Edward G. Robinson, by reason of the above-mentioned occurrences, has demanded of the undersigned corporation that it give him full protection on the set from bodily harm and insulting demeanor from Mr. George Raft, making the position of the Company an extremely difficult one in its effort to produce a photoplay of artistic merit under the circumstances shown...

The undersigned feels that the above occurrences are of such serious import that they should be officially called to the attention of the Screen Actors Guild...

Yours very truly,

WARNER BROS. PICTURES, INC.

By: Roy Obringer

|

| Above and below: two scenes from Manpower with its three leading actors Robinson, Dietrich and Raft. The film became a solid box-office success despite the problems on the set. |

Source of the letter: Inside Warner Bros. (1935-1951) (1985), selected, edited and annotated by Rudy Behlmer.