By the early 1960s, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford were no longer the big box-office stars they once were. Both in their fifties, the actresses desperately needed a project to revive their declining careers. It was director/producer Robert Aldrich who came to the rescue when he sent Joan a copy of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, a 1960 novel by Henry Farrell. For years Joan had asked Aldrich, with whom she had worked on Autumn Leaves (1956), to find a suitable project for her and Bette Davis (Bette and Katharine Hepburn being the actresses she admired most). Joan was very enthusiastic after reading Farrell's story and next asked Bette to co-star with her in the film.

In order to get financing for his project, Aldrich approached every studio in Hollywood but the studio moguls had little faith in the box-office appeal of the two older stars. In the end, independent production company Seven Arts agreed to finance the film and Warner Bros, after being initially reluctant, decided to distribute it. Baby Jane was made on a very modest budget —with production completed in a mere six weeks— and Bette and Joan received salaries that were much lower than their standard fees. Aldrich later recalled: "I offered each actress a percentage of the picture plus some salary. Joan accepted, but Bette's agents held out for more than I could pay". Eventually Joan was paid a salary of $30,000 plus 15% of the net profits while Bette received $60,000 (double of Joan's salary!) and 10% of the profits. Being paid in net profits, Bette compared it to gambling and, as it turned out, Joan proved to be the better gambler. Unexpectedly, Baby Jane became a massive box-office hit and, with her percentage of the profits being higher than Bette's, Joan ultimately earned much more than Bette. (According to Donald Spoto's Possessed: The Life of Joan Crawford (2010), Joan's earnings on Baby Jane amounted to $1,400,000.)

|

| Above: Bette Davis and Joan Crawford in a publicity still for Baby Jane as resp. Baby Jane Hudson and her sister Blanche. From the start Joan had wanted to play the role of the wheelchair-bound sister while she felt Bette would be perfect as the insane Baby Jane. Below: Joan and Bette laughing on the set of Baby Jane. While the women were by no means friends, they reportedly got along during filming despite all gossip to the contrary. It was, however, when Bette received an Oscar nomination for her performance and Joan didn't that things turned unfriendly between them (read more in this post). |

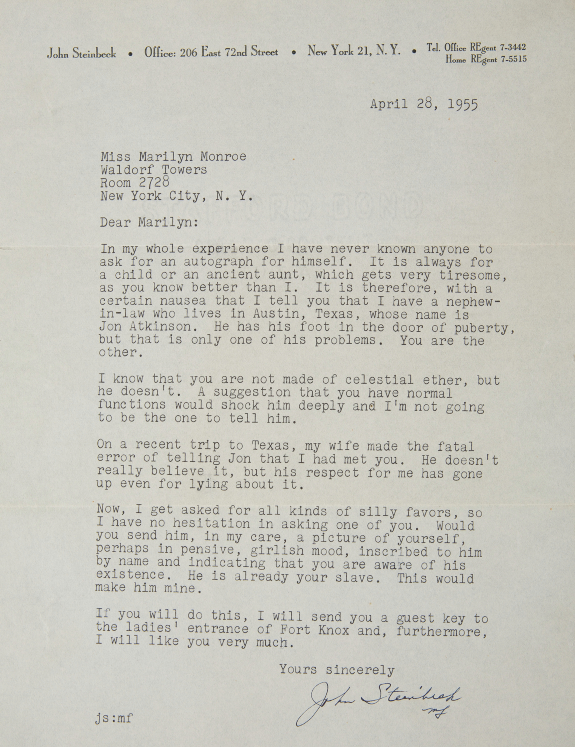

Below is the first page of Bette and Joan's contracts for Baby Jane. Under paragraph 3 their salaries are indicated. Joan's contract clearly shows that she was paid $30,000 and not $40,000, as I've seen mentioned in several sources. The film of writer/producer Luther Davis referenced in the second paragraph of Joan's contract was Lady in a Cage (1964); at the time Joan was being considered for the lead role, which eventually went to Olivia de Havilland.

|

| Above: Bette made sure that in the opening credits of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? her name came before Joan's. |

Concluding this post, here is a fun anecdote. In November 1962 Bette Davis appeared on

The Jack Paar Program to promote

Baby Jane. Bette told Paar that when she and Joan were first suggested for the leads, the studio moguls said they wouldn't give a dime for "those two old broads" (watch Bette with Jack Paar

here). A few days later, Bette received a note from Joan saying: "

Please do not continue to refer to me as an old broad. Sincerely, Joan Crawford."

|

| "Those two old broads" |