.jpg) |

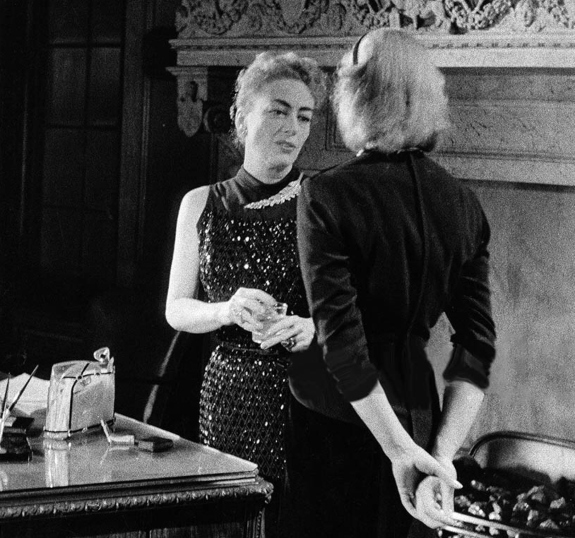

| Victor Fleming and Ingrid Bergman on the set of Joan of Arc |

|

| Fleming and Bergman fooling around while filming Joan of Arc |

.jpg) |

| Bergman and her first husband Petter Lindström |

Fleming wrote several love letters to Bergman, two of them seen below. According to Alan Burgess (Ingrid's co-author on her 1980 memoir), Bergman never protested against Fleming's declarations of love as she felt that "it was all part of the flood of creation".

(written on the envelope) This was in my pocket when I arrived. Several more I destroyed. The Lord only knows what is written here, and no doubt His mind is a little hazy because he had not a very firm grip upon me at the time I was writing —we were slightly on the "outs". I was putting more trust in alcohol than in the Lord. And now I am putting all my trust in you when, without opening this, I send it, for you may think me very foolish.

(letter inside the envelope) Just a note to tell you dear— to tell you what? That it's evening? That we miss you? That we drank to you? No—to tell you boldly like a lover that I love you—cry across the miles and hours of darkness that I love you—that you flood across my mind like waves across the sand. If you care—or if you don't, these things to you with love I say. I am devotedly—your foolish—ME.

_____

Dear and darling Angel,

How good to hear your voice. How tongue-tied and stupid I become. How sad for you. Then when you put the phone down, the click is like a bullet. Dead silence. Numbness and then thoughts. Thoughts that beat like drums upon my brain. My heart, my brain. I hate and loathe both. How they hurt and torment me— pain my flesh and bones. When they have had their fill of that, they quarrel and fight each other. My brain beats my heart into a great numbness. Then my brain pounds my heart to death. All this I can do nothing about.

In Arabian Nights it says: "Do what thy manhood bids thee do. From none but self expect applause. He best lives and noblest dies, who makes and keeps his self-made laws."Time stopped when I got aboard that train. It became dark and in the darkness I was lost. Why I did not think to do some drinking I don't know. I went to bed for fourteen hours and I slept fourteen minutes, forgot to order breakfast on the Century, and had no food or coffee until 1 p.m. That much I remember. Someone met me at the train. I'm very much afraid she found me crying. A hundred years old and crying over a girl. I said, "There's no fool like an old fool."

Sources: Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (2008) by Michael Sragow and Ingrid Bergman: My Story (1980) by Ingrid Bergman and Alan Burgess.

Released in November 1948, Joan of Arc received mixed reviews while failing at the box-office. The film was Victor Fleming's final achievement. On 6 January 1949, while at home sitting in a chair, Fleming suddenly collapsed and died of a heart attack en route to the hospital. Bergman said that Fleming had worn himself out making Joan of Arc, anxious to make the film a success knowing how much Joan of Arc meant to her. The actress was deeply saddened by Fleming's passing and, according to Alan Burgess, felt a certain responsiblity, wondering whether the pressures of the film had contributed to his untimely death. Fleming, best known for directing the 1939 classics Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, was 59 years old.

|

| 10 November 1948, Ingrid Bergman is escorted by Victor Fleming to a benefit performance of Joan of Arc, given for the United Hospital Fund. |