Norma Shearer was one of the first serious contenders for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in David O. Selznick's Gone with the Wind (1939). On 21 March 1937, Walter Winchell, a famed newspaper gossip columnist and radio commentator, reported that Selznick desperately wanted her to play Scarlett. The announcement evoked a public response which was overwhelmingly negative. People felt that Norma, at the time a major MGM star, was not at all right for the part; while some could see her play Melanie, Scarlett she was not.

|

| Above: Norma Shearer as the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning in a publicity still for The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934). Below: Norma playing a loose woman in A Free Soul (1931), the first of three films she made with Clark Gable. |

Two days prior to Winchell's announcement, Kay Brown (Selznick's representative and talent scout) had sent a memo to her boss, sharing the opinions on Norma Shearer of several people, including GWTW's author Margaret ('Peggy') Mitchell. Like the general public, none of them was enthusiastic about Norma playing Scarlett, feeling she was "not the type". Brown believed that the actress was being associated too much with her "good girl" roles in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) and Romeo and Juliet (1936), despite having also played less virtuous characters in films like A Free Soul (1931) and Riptide (1934).

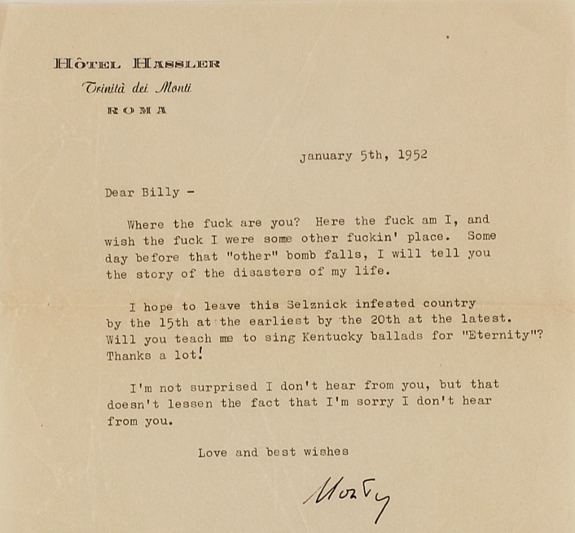

Transcript:

TO Mr. David O. Selznick

FROM Miss Katharine Brown

DATE March 19, 1937

SUBJECT NORMA SHEARER

Dear David:

I am sorry to make this kind of report on Miss Shearer, as I was so terribly in favor of the idea when it was first discussed.

I selected three people, as we decided on the telephone, one of whom is the editor of RedBook, Edwin Balmer; Lois Cole of Macmillan, and a rank outsider to the picture business.

The suggestion in each case proved a shock and the response was "but, she's not the type." Then, as I advanced arguments about the fact that she is a great actress and could play Scarlett, they warmed up to the idea.

Mr. Balmer thought her selection would be analyzed as a compromise. They didn't feel that she could hurt the picture, but nobody reacted enthusiastically. This was all a great disappointment to me.

Peggy Mitchell was scared to death to say anything at first, but I reassured her that her conversation would be only for your ears. She, too, was very lukewarm; not against her but, like the others, not enthusiastically excited about the idea.

Shearer seems to be tied up with pictures like JULIET and ELIZABETH BARRETT. People forget her first great success in THE FREE SOUL and RIPTIDE. Shearer does not seem to be associated with sex. Both Balmer and Mitchell said you couldn't imagine Shearer killing in cold blood and bargaining her body.

Everybody says get someone with no name so Scarlett can be Scarlett and it won't be Miriam Hopkins making believe she is Scarlett, just as if we weren't all half crazy trying to do this!

(signed) Kay

On 30 March 1937, following Winchell's announcement and the public outcry it had caused, both Selznick and Norma issued statements in which they denied Norma being a candidate for Scarlett. Selznick said: "Miss Norma Shearer and we of Selznick International have jointly come to a conclusion against further consideration of the idea of Miss Shearer playing the role of Scarlett O'Hara in "Gone with the Wind". Miss Shearer has made other arrangement, and we are continuing the search begun several months ago, and never interrupted, for an unknown, or comparatively unknown, actress for the part ..." And Norma said: "... I have other plans, which I cannot divulge at this time, which preclude my giving the idea any further consideration. I shall be watching with great interest to see who Mr. Selznick selects and whether she will be a well known star or a newcomer. I know she will be wonderful, and I will be wishing her luck."

|

| Dallas Morning News, 24 June 1938 |

Despite these statements, Norma's

GWTW adventure did not end here. About a year later, the actress would again be a contender for the role of Scarlett. In fact, on 24 June 1938, several newspapers announced that she had already been cast, including

The New York Times and

The Dallas Morning News. And again, like Walter Winchell's announcement had done a year earlier, this announcement also evoked a great many negative reactions from people who felt Norma was unsuited for the role. On top of that, people were shocked by the fact that she had asked Selznick to change the script in order to make Scarlett more sympathetic. (In a previous post, I reproduced four of the many letters that Selznick received regarding Norma's casting as Scarlett; you can read them

here.) Ultimately, due to public pressure, Norma withdrew from the picture and gave up the role for good.

In November 1938, several months after giving up Scarlett, Norma wrote the following letter to Marjory Pollock, one of her fans who had been in favour of her playing Scarlett. Norma reflects on her decision not to play the part and in particular talks about the traits of Margaret Mitchell's heroine that had bothered her.

.jpg)

Source: Bonhams

Transcript:

November 10, 1938.

Dear Marjory Pollock:

Reading some of the thousands of letters that came in after the announcement that I would play Scarlett O'Hara, I find your gracious note. I am so happy to know that you wanted me to play the role, even tho I have decided against it. Your confidence in me is most inspiring.

When the studio asked me if I would accept the role, I gave it careful consideration; but I was troubled by traits - such as her disrespect for the death of her husband, her neglect of her child, her marriage to a man for whom she even had no respect, her indifference to the revelation of Rhett Butler's love at the end of the story - which I knew would be unpleasant to portray on the screen. I think any woman - no matter how hard she has been - must be redeemed by such a great love as Rhett's.

It has always been my desire to vary my roles, as you know, but I felt I had been associated with such idealistic characters in the past few years that to play Scarlett whole-heartedly might be offensive and leave an unpleasant impression on the minds of the public.

I was so glad to read that your father recovered so completely from his illness, and the nice things he said about me were most pleasant to listen to.

My sincere appreciation, and good wishes to you both,

(signed) Norma Shearer

Miss Marjory Pollock,

Fine Arts School,

South Bend, Indiana.

|

| Norma Shearer and Clark Gable at a Hollywood event in 1938; they played in three films together (i.e. A Free Soul (1931), Strange Interlude (1932) and Idiot's Delight (1939)) but their fourth was not to be. Instead of Shearer, Vivien Leigh would star in GWTW in her only pairing with Gable. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_03%20(1).jpg)

_NRFPT_01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)