|

| George Cukor flanked by his leading actors Spencer Tracy and Deborah Kerr on the set of Edward, My Son |

.jpg) |

| George Cukor and Cole Porter |

.jpg) |

| Francis (l) and Hopkins |

|

| George Cukor flanked by his leading actors Spencer Tracy and Deborah Kerr on the set of Edward, My Son |

.jpg) |

| George Cukor and Cole Porter |

.jpg) |

| Francis (l) and Hopkins |

From the mid-1940s until the early 1950s, Jeanne Crain was one of the biggest stars at 20th Century-Fox. After signing a long-term contract with Fox in 1943, Crain made her (uncredited) debut in the musical The Gang's All Here (1943). Her first substantial role was in the horse racing drama Home in Indiana (1944), followed by roles in Winged Victory (1944) and in such box-office hits as the musical State Fair (1945) —opposite Dana Andrews, with her singing voice dubbed— and the film noir Leave Her to Heaven (1945) playing the good sister to Gene Tierney's bad one. By 1946, Crain had become one of the studio's main box-office draws. The actress received more fanmail than anyone on the Fox lot (except for Betty Grable) and was also a personal favourite of studio head Darryl F. Zanuck.

Since Crain was a big Fox star, Zanuck wouldn't let her play the relatively small role of Clementine in John Ford's western My Darling Clementine (1946). In the memo below, Zanuck informs director Ford of his decision not to cast Crain in the part, which eventually went to newcomer Cathy Downs. According to John Ford biographer Ronald L. Davis, the director later responded to Zanuck's memo, saying he didn't care much who played Clementine, "providing she doesn't look like an actress".

DATE: February 26, 1946

TO: Mr. John Ford

CC: Sam Engel [producer]

SUBJECT: MY DARLING CLEMENTINE

Dear Jack:

There will be no chance for us to get Jeanne Crain to play in My Darling Clementine. I know she would be delighted to be directed by you but the part is comparatively so small that we would be simply crucified by both the public and critics for putting her in it. She is the biggest box-office attraction on the lot today. There is no one even second to her ...

D.F.Z.

Source: Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years At Twentieth Century-Fox (1993); selected and edited by Rudy Behlmer.

|

| Crain with Zanuck and his children |

|

| Audrey Hepburn knitting on the set of The Unforgiven |

|

| Audrey Hepburn recovering in the hospital following her horse riding accident, with husband Mel Ferrer by her side. |

|

| Director John Huston with Lillian Gish behind the scenes of The Unforgiven |

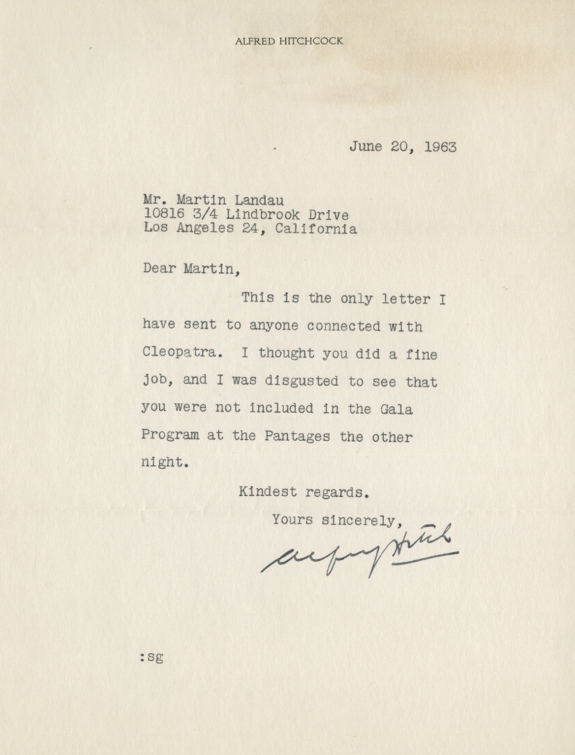

Martin Landau began his acting career in the late 1950s. At one time a student at Lee Strassberg's prestigious acting studio and a good friend of James Dean, Landau made his Broadway debut in Middle of the Night in 1957. His first important screen appearance was in a supporting role in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959), playing James Mason's creepy henchman. Other film roles followed, including supporting roles in the epics Cleopatra (1963) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965). Landau's big breakthrough occurred on television, however, with leading roles in the series Mission: Impossible (1966–1969) and Space: 1999 (1975–1977). The late 1980s saw a revival of the actor's film career when he was cast in Francis Ford Coppola's Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) and Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), both roles earning him Oscar nominations for Best Supporting Actor. Landau's only Oscar win came several years later for his portrayal of Bela Lugosi in Tim Burton's Ed Wood (1994), starring opposite Johnny Depp who played Ed Wood. Landau continued to act in both film and television productions until his death in 2017, aged 89.

|

| Source: Heritage Auctions |

|

| Landau with Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra |

|

| Hitchcock and Landau on the set of North by Northwest |

.jpg) |

| Source: Heritage Auctions |

%20(1).jpg) |

| Landau and Johnny Depp in Ed Wood (l) and Sir Anthony Hopkins |

In late September 1948, Preston Sturges' The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend (1949) was about to go into production and Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck had just received the sketches for Betty Grable's wardrobe from costume designer René Hubert. In the following memo to Sturges, Zanuck asks for the director's opinion regarding the finale of the film. Zanuck wanted to show more of Grable's legs, something they had failed to do in The Shocking Miss Pilgrim (1947). For the finale he suggests to have someone step on Grable's skirt, so that it comes off and the actress' legs are shown. While this was eventually incorporated into the scene, it didn't help the picture which did poorly at the box-office.

DATE: September 20, 1948

TO: Preston Sturges

SUBJECT: THE BEAUTIFUL BLONDE FROM BASHFUL BEND

Dear Preston:

I looked at the wardrobe sketches this afternoon that René Hubert has for Betty and I think they are wonderful, particularly the first red dress. The main reason I wanted to see them is that once when we made a picture called The Shocking Miss Pilgrim we did not show Grable's legs in the picture and in addition to receiving a million letters of protest the incident almost caused a national furor.

I am glad that he has given her a split skirt, at least in the opening, and that later on we see her in her panties.

Right now, I have thought of another idea that I would like to get your reaction on:

Suppose in the fight to the finish she is wearing a simple two-piece suit, something like a bolero jacket with a long skirt. Someone steps on the skirt and it tears off in the start of the battle royal ...

Perhaps you have some other suggestion. I know it perhaps sounds like a silly thing to worry about, but from a commercial standpoint Betty's legs are no joking matter.

D.F.Z.

Source: Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years At Twentieth Century-Fox (1993); selected and edited by Rudy Behlmer.

Incidentally, I recently watched The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend at the recommendation of my sister who thoroughly enjoyed it and I must say, despite the film's bad reputation, I enjoyed it too. Admittedly, The Beautiful Blonde doesn't rank among Sturges' finest but the film —about a trigger-happy saloon singer who hides out in the tiny town of Bashful Bend after shooting a judge in the butt— is still good fun. I'm not too familiar with Betty Grable but she is delightful here and looks great in René Hubert's colourful costumes. Grable herself reportedly hated the film.

%20(1).jpg) |

| Betty in the finale of The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend after someone has stepped on her dress, tearing off the skirt and exposing Betty's legs. |

.jpg) |

| Betty and Preston Sturges on the set of The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend |

Linda Darnell hated the Hollywood social scene and made only one close friend in Hollywood, actress/dancer Ann Miller. As young starlets the two had first met at a benefit on Catalina Island and immediately got along. They had much in common, both being from Texas and having started their careers at a very young age. They both lived with their mothers, who also befriended each other. Linda and her mother Pearl often visited the Millers up in the Hollywood Hills. "While the two mama hens clucked," Ann recalled, "we would gossip about our two studios and all the goings-on there." (Linda was under contract to 20th Century-Fox while Ann had signed with Columbia.) The close friendship between Linda and Ann lasted for decades until Linda's untimely death in April 1965.

|

| Linda Darnell (l) and Ann Miller |

The story of Linda Darnell's death is a tragic one. Linda was staying at the home of her friend and former secretary Jeanne Curtis when the house caught fire. The women had stayed up late watching one of Darnell's old films on television (the 1940 Star Dust) and afterwards went upstairs to go to bed. They woke up to the fire, which had started in the living room. Curtis and her daughter escaped through the second-floor window while Linda, who was too afraid to jump, had gone downstairs trying to escape through the front door. Firemen eventually found her lying behind the living room sofa, still alive but with burns over 90% of her body. Immediately rushed to the hospital, the actress underwent surgery but ultimately couldn't be saved. On 10 April 1965 —thirty-three hours after the fire— Linda Darnell passed away, only 41 years old.

_______

While Darnell was in the hospital, letters, cards and telegrams from all over the world came pouring in to wish her well. Her friend Ann Miller sent her the following telegram, still hoping and praying Linda would recover.

Dearest Linda. If there's anything that Mom and I can do, we'll be there to help. In my heart you are my dearest friend in the whole world and always will be. We are saying prayers for your recovery. Love, Annikat and Mommikat.

After Linda's death, Ann sent another telegram. The telegram was read during the second memorial service held in Burbank on 8 May 1965.

To my dear friend Linda, lover of life and of people, a giver and not a taker. You will always live in our hearts. Farewell Tweedles. Love always, Annie and Mother K.

Source: Hollywood Beauty: Linda Darnell and the American Dream (1991), by Ronald L. Davis.

|

| Source: Gotta Have Rock and Roll |

|

| Source: Gotta Have Rock and Roll |

.jpg) |

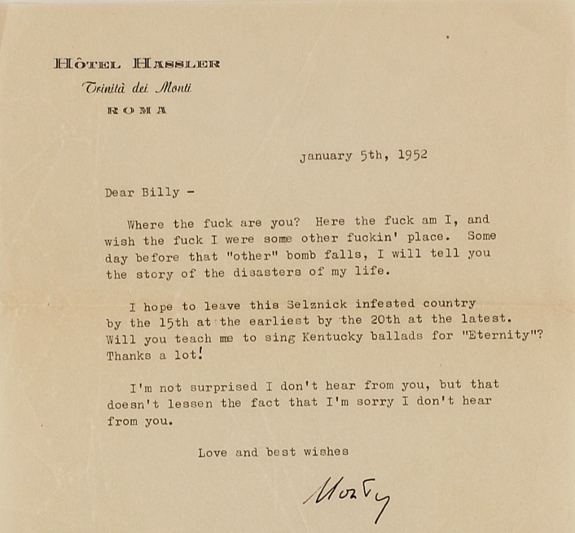

| David Selznick and Monty Clift |

In the summer of 1938, Warner Bros. cast Claude Rains as a tough New York City cop in They Made Me a Criminal, a Busby Berkeley film starring John Garfield in the lead as a boxer wrongly accused of murder. Rains, who had signed a long-term contract with Warners in November 1935, considered himself unsuited for the role and did not want to play it. Requesting to be released from the film, the actor sent studio boss Jack Warner a telegram on 31 August 1938. The role would do nothing to advance his career, Rains thought, and his miscasting could only hurt the picture.

|

| Claude Rains, John Garfield and Billy Halop (of The Dead End Kids) in a scene from They Made Me a Criminal. |

August 31, 1938

Jack WarnerVice President, Warner BrothersFirst National PicturesDear Jack. Having thoroughly enjoyed my association with the studio and toed the line to cooperate to the best of my ability, I feel that you should know of my inability to understand being cast for the part of Phelan in "They Made Me a Criminal." Frankly, I feel that I am so poorly cast that it would be harmful to your picture. You have done such a good job in building me up that it seems a pity to tear that down with such a part as this, and I am confident that your good judgment will recognize this. Dogs delight to bark and bite and I think I have been a good dog for three years, so perhaps you will give me five minutes to talk it over.

Claude

Source: Inside Warner Bros. (1935-1951) (1985), selected and edited by Rudy Behlmer.

When Warner threatened Rains with suspension, the actor accepted the role and indeed —I must agree with Rains and the general opinion— he was terribly miscast. (But I don't think he harmed the picture, considering how little screentime he had.) Later Rains said that of the films he had made They Made Me a Criminal was one of his least favourites.

In her 1990 autobiography Ava: My Story, Ava Gardner said that Frank Sinatra was the love of her life. The two had met in 1943 at a Hollywood nightclub and, after seeing each other only occasionally over the years, met again at a party in 1949. They started an affair, with Sinatra still married to his first wife Nancy Barbato (with whom he had three children). On 7 November 1951, ten days after Sinatra's divorce had come through, Ava and Frank tied the knot, entering into a very tumultuous and highly publicised marriage. The two were both —in Ava's own words— "high-strung people, possessive and jealous and liable to explode fast", their temperaments often leading to heated fights, sometimes even in public. During their marriage, Ava got pregnant with Sinatra's child twice but in both cases had an abortion. On 29 October 1953, after two years of marriage, the couple formally announced their separation, with the divorce eventually being finalised in 1957. Ava and Frank remained good friends until Ava's death in 1990, at age 67.

|

| Ava Gardner and Frank Sinatra, who was Ava's third and final husband (Artie Shaw and Mickey Rooney being husband number one and two). |

|

| Irving Thalberg, Lillian Gish and Louis B. Mayer in 1926 |

.jpg) |

| Thalberg won the Oscar for Best Picture for Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), here photographed with Clark Gable and director Frank Capra at the Oscars of 1936. Click here to see and hear Thalberg accept the award from Capra. Thalberg had won the Best Picture Oscar twice before, for The Broadway Melody (1929) and Grand Hotel (1932). |

Dear Irving:

I cannot permit you to go away to Europe without expressing to you my regret that our last conference had to end in a loss of temper, particularly on my part. It has always been my desire to make things as comfortable and pleasant for you as I knew how, and I stayed away from you while you were ill because I knew if I saw you it was inevitable that we would touch on business, and this I did not want to do until you were strong again. In fact I told Norma [Shearer] to discourage my coming to see you until you felt quite well.

It is unfortunate that the so-called friends of yours and mine should be only too glad to create ill feeling, and attempt to disrupt a friendship and association that has existed for about ten years. Up to this time they have been unsuccessful, but they have always been envious of our close contact and regard for each other.

If you will stop and think, you cannot mention a single motive or reason why I should cease to love you or entertain anything but a feeling of real sincerity and friendship for you. During your absence from the Studio, I was confronted with what seems to me to be a Herculean task, but the old saying still goes —“The show must go on.” Certainly we could not permit the Company to go out of existence just because the active head of production was taken ill and likely to be away from the business for a considerable length of time. I, being your partner, it fell to my lot, and I considered it my duty and legal obligation under our contract, to take up the burden anew where you left off, and to carry on to the best of my ability . . . .I regret very much that when I last went to see you to talk things over I did not find you in a receptive mood to treat me as your loyal partner and friend. I felt an air of suspicion on your part towards me, and want you to know if I was correct in my interpretation of your feeling, that it was entirely undeserved. When I went to see you I was wearied down with the problems I have been carrying, which problems have been multiplied because of the fact that the partner who has borne the major portion of them on his shoulders, was not here. Instead of appreciating the fact that I have cheerfully taken on your work, as well as my own, and have carried on to the best of my ability, you chose to bitingly and sarcastically accuse me of many things, by innuendo, which I am supposed to have done to you and your friends. Being a man of temperament, I could not restrain myself any longer, and lost my temper. Even when I did so I regretted it, because I thought it might hurt you physically.

Regardless of how I felt, or what my nervous condition was, I am big enough to apologize to you, for you were ill and I should have controlled my feelings.

I am doing everything possible for the best interests of yourself, Bob [MGM attorney Robert Rubin], myself, and the Company, and I want you to know just how I feel towards you; and, if possible, I want you to divest yourself of all suspicion, and believe me to be your real friend, and to know that when I tell you I have the greatest possible affection and sincere friendship for you, I am telling the truth.

I hope this trip you are about to make will restore you to even greater vigor than you have ever before enjoyed, and will bring you back so that we may work together as we have done for the past ten years.And now let me philosophize for a moment. Anyone who has said that I have a feeling of wrong towards you will eventually have cause to regret their treachery, because that is exactly what it would be, and what it would be on my part if I had any feeling other than what I have expressed in this letter towards you. I assure you I will go on loving you to the end.

I am going to take the liberty of quoting a bit of philosophy from Lincoln. This is a quotation I have on my desk, and one which I value highly: “I do the very best I know how, and the very best I can, and I mean to keep doing so until the end. If the end brings me out right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything. If the end brings me out wrong, ten angels swearing I was right, will make no difference.”

I assure you, Irving, you will never have the opportunity of looking me in the eye and justly accusing me of disloyalty or of doing anything but what a good friend and an earnest associate would do for your interest, and for your comfort.

If this letter makes the impression on you that I hope it does, I should be awfully glad to see you before you go and to bid you Bon Voyage. If it does not, I shall be sorry, and will pray for your speedy recovery to strength and good health.

With love and regards, believe me,

Faithfully yours,Louis

Thalberg responded two days later.

Dear Louis:

I was deeply and sincerely appreciative of the fact that you wrote me a letter, as I should have been very unhappy to have left the city without seeing you. I was indeed sorry that the words between us should have caused on your part a desire not to see me, as I assure you frankly and honestly they did not have that effect on me. We have debated and disagreed many times before, and I hope we shall many times again. For any words that I may have used that aroused bitterness in you, I am truly sorry and I apologize.

I’m very sorry that I have been unable to make clear that it has not been the actions or the words of any—as you so properly call them—so-called friends, whose libelous statements were bound to occur, that have in any way influenced me. If our friendship and association could be severed by so weak a force, I am sure it would long ago have been ruptured by that source. There are, however, loyalties that are greater than the loyalties of friendship. There are the loyalties to ideals, the loyalties to principles without which friendship loses character and real meaning, for a friend who deliberately permits the other to go wrong without sacrificing all—even friendship—has not reached the truest sense of that ideal. Furthermore, the ideals and principles were ones that we had all agreed upon again and again in our association, and every partner shared equally in the success that attended the carrying out of those principles.

I had hoped that the defense of those principles would be made by my three closest friends [presumably Mayer, Schenck and Rubin]. I say this not in criticism, but in explanation of the depths of the emotions aroused in me, and in the hopes that you will understand. I realize with deep appreciation the effort you have been making for the company and in my behalf, and no one more than myself understands the strain to which you are subjected.

Believe me, you have my sympathy, understanding and good wishes in the task you are undertaking; and no one more than myself would enjoy your success, for your own sake even more than for the sake of the company.

Please come to see me as soon as it is convenient for you to do so, as nothing would make me happier than to feel we had parted at least as good personal friends, if not better, than ever before.

Irving

Source: Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince (2009), by Mark A. Vieira

Despite their broken friendship, Thalberg and Mayer remained civil and polite to each other, at least in their letters. Not only the letters above show the courtesies between them, but also the following letter written by Mayer to Thalberg on 31 December 1933. Mayer expresses his wish to "get closer and closer in [his] association" with Thalberg in the new year, and also says he will do anything to make Thalberg's work "light and pleasant". However, it was Mayer who stonewalled Thalberg in preparing his first films as a unit producer. Thalberg found that writers and actors he wanted to work with were suddenly unavailable, assigned elsewhere by Mayer. Also, Mayer had blocked Thalberg's access to MGM's best directors, so for Riptide (1934) Thalberg had to look outside the studio and eventually hired freelancer Edmund Goulding.

|

| Thalberg with wife Norma Shearer and Mayer in 1932 |